Who doesn’t dream of donning a fedora and leather jacket, grabbing a 10-foot, 12-plait bullwhip, and diving into the nearest cave in search of treasure, danger, and adventure? Who doesn’t want to look like an Average Joe on the outside, but secretly be a professor of archeology on the inside, and even more secretly be a globetrotting daredevil?

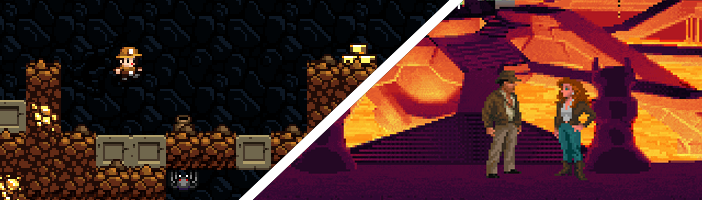

There are a bunch of games out there that let you do the whip-wielding archeologist thing, but most of them aren’t that great. Two very good ones though, are Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, released by LucasArts in 1992, and Spelunky, released by Derek Yu seventeen years later (that’s 2009, for the mathematically challenged).

The fascinating thing about these two games is that they are quite similar in terms of theme and mood: both do a fantastic job of imparting that sense of earth-encrusted derring-do—both make me feel like an armchair Indiana Jones—and yet the mechanics that make the games tick are very, very different. Fate of Atlantis is a classic point-and-click adventure game, filled with puzzles and featuring a well-developed but mostly linear plot; Spelunky, by contrast, is a an action-platformer-roguelike with procedural level generation, whose player-created story arcs are less defined, and never go the same way twice.

As I recently finished playing through Fate of Atlantis for the second time, after fourteen years away (you can download the game for $5 from Steam now, which is great), I was struck that these games, with their similar themes yet different mechanics, present a great opportunity to compare and contrast two breeds of interactive experience.

Aesthetic

First, let’s examine look and feel. The aesthetic of both games is vivid and compelling: both games rely on pixel art, and both are fine examples of the art form. Fate of Atlantis is especially impressive in that way that few games made after 1995 are: it presents sprawling room after sprawling room of pixeled mosaics drawn entirely from a two hundred and fifty six color pallet. Why, oh why don’t we paint like this anymore?

I first played Fate of Atlantis in 1995, when I was twelve years old, and so the game has some nostalgic draw. That being said, most things we remember nostalgically don’t hold up all that well when we dust them off and take them for another spin (which is why people generally like to remember and talk about the things they miss, but not actually re-experience those things). I prepared myself for disappointment with FoA, but it turns out that I needn’t have: the game impressed me greatly, not least with its look and feel.

Clearly I’m a sucker for pixel art. Partly, perhaps, for nostalgic reasons; partly because there’s just a dearth of large-scale pixeled games these days, and I like visual variety; but mostly, I think, because pixel art has a unique connection to the elements that make computer games up. I suppose it’s the formalist in me, but there’s something wonderful about blatantly incorporating the nature of computer displays into a game, rather than trying to cover up that nature.

Also, in the case of Spelunky and FoA, the rough, mosaic-y texture of the pixels seems especially appropriate to the games’ themes of archeology and exploration. The idea of a perfectly lit, glossy, 3D model of Indiana Jones strikes me as a bit obscene.

Spelunky doesn’t have the same awe-inspiring quality about its visuals that FoA does, just because it is a level-based procedural game that makes use of the same graphics again and again (and it’s a one-man show, at that). It is, rather, the attention to detail that makes Spelunky’s look and feel stand out. Everywhere that Yu could have made due with a motionless sprite he has instead provided a thoughtful animation; everywhere that you might expect the graphics library to run out you find some new little pixelated gem. Indeed, where Yu could have easily used a single look for his game’s world, he has instead incorporated four entirely different graphical sets, making each of the game’s four groups of four levels feel like an entirely new universe. It is this kind of detail that, in Yu’s words, “makes me feel like I’ve been stuffed into the warm belly of a Taun Taun after spending hours on the cold, frozen surface of Hoth.” I just can’t say it any better than that.

In similar fashion to the pixel art, the music for both games is of a retro (midi) style, and while generally nice, I’m not as sure that it couldn’t be updated to something more technologically contemporary in either case (it would bruise my nostalgia, but would it do anything worse?). The question, I suppose, is whether the musical style is as inherently tied to the medium and the themes as the pixels seem to be. Perhaps it’s just me, but I find that midi music can start to grate on my ears after a while—even if it is, in the case of Fate of Atlantis, the genuine music of John Williams.

Story

Both games, in the course of a single play, tell a story. In Fate of Atlantis the story goes like this:

It’s 1939, a few months before World War II. Dr. Henry “Indiana” Jones Jr., at the request of a certain Mr. Smith, retrieves a strange idol from the Barnett College museum. However, when Indy presents it to Smith, Smith holds him at gunpoint, takes the statue and escapes.

Indy and his friend Marcus Brody find out that “Smith” is in fact Klaus Kerner, an agent of the Third Reich (surprise surprise) who’s interested in a certain excavation in Iceland, where Indy and an ex-colleague of his, Sophia Hapgood, once worked on an archaeological expedition. Kerner’s second target is Sophia, who lost her interest in archeology and became a psychic, giving seminars about Atlantis and communicating with the Atlantean god-king Nur-Ab-Sal.

Indy goes to New York City and meets up uneasily with Sophia while she is giving a speech. The two find that Klaus has already been there, and ransacked Sophia’s room. All her artifacts are stolen except a certain necklace, which she always wears. Sophia explains that the Nazis are after the power of Atlantis because of orichalcum, a legendary metal purported to be more powerful than uranium. The German Army, led by Kerner and mad scientist Dr. Hans Ubermann are after the element in order to utilize it as an unlimited source of energy. The key to finding Atlantis is believed to be a lost dialogue of Plato, called the “The Hermocrates”… (Slightly adapted from Wikipedia).

I quote Wikipedia at length here to emphasize the kind of traditional story arc and cinematic narration employed in FoA. Spelunky, by contrast, lacks any kind of prewritten script, save for the half-prewritten procedural introduction to the game, which shows our hero entering a cave, and randomly puts together lines of text from a predefined pool, creating an introduction that might go like this: “As the moon burned bright above/I furrowed my brow/And that’s when it all started.” Or alternately like this: “After I double checked my map/I furrowed my brow/And swore I heard voices up ahead.”

After this brief intro, the game, in one play, servers up a sequence of sixteen procedurally generated platform levels that are never the same twice. So Spelunky tells not one story, but many, and they are all emergent. These stories are less intricate than the single story which Fate of Atlantis tells, and they lack a predefined arc, but they can nonetheless be surprisingly compelling. If we were to jump into the middle of one, narrated in first person, it might go something like this:

The level exit is within sight. A careful downward leap will see both me and the blonde damsel I’m carrying in both arms to the next world. Only a single trap stands in my way: a gargoyle mouth that will belch out an arrow the moment I drop past it, skewering me and easily wiping out my last bit of health. If only I could throw something else at the trap to set it off prematurely … but I’m out of bombs, and there’s nothing nearby to throw. Nothing save for the helpless maiden weighing me down, anyway.

Hmm.

She plummets downward like a rock, triggering the trap and taking an arrow point-blank to the face. The force of the impact sends her body bouncing across the cave floor until it lands on a rather surprised snake, instantly crushing it to death. I pause to mourn her as I drop down safely to the exit, but only for a moment - I’ve still got 15 more procedurally-generated floors to go (The Escapist).

… Fate of Atlantis

The creators of Fate of Atlantis take much the same approach to storytelling as the writers of any book or film: a plot is conceived, fleshed out, and allowed to run from start to finish. The development of likeable characters, a balanced story arc, build-up, climax, and down-time are all, to some extent at least, taken into consideration. The final product pulls you in like any well-conceived piece of fiction: the only difference being that the pace of the story is in your hands, and will progress as quickly or as slowly as you can pick up inventory items and determine where they must be used.

This difference is a big one though, because it means that passive consumption is no longer an option as it is with literature, or film, and this forced interaction often serves to make you more invested in the work than you might otherwise be (say, for example, if you were to watch someone else play the game).

Still, it must be emphasized that in FoA the element of interactivity is essentially limited to this ability to control pacing by solving puzzles—and that most puzzles are not optional, and that your ability to “control” the pacing is really determined by how adept you are at solving the kinds of puzzles common to graphic adventure games: if you are a veteran of the genre the story will move quickly; if a novice, it will take you more time to advance the plot.

Fate of Atlantis deserves commendation for attempting to get around the linearity of this classic adventure game approach by presenting three unique “paths” that the player can choose from midway through the game. While you will end up visiting most of the same locations regardless of which option you choose, the puzzles presented are very different, and the story’s arc is somewhat changed. A considerate move that does soften the hard edge of the game’s determinism to some extent, but only slightly: having the three obvious path options inevitably encourages many players to play the game three times, and while this replay value may seem positive, it also destroys the main significance of having the three path options to begin with, which is to make the player wonder what would have happened “if…”. The free will we possess as human beings—illusory or not—is dependent on uncertainty, on paths unexplored: the fact that we can choose one thing, and then have one experience, and never go back to have the other. By contrast, if you choose to explore all three paths in Fate of Atlantis, then any illusion the game has cast to make you believe that you can choose your own story is effectively destroyed: the game becomes, once again, a single linear entity which includes inside itself three linear paths, all with known outcomes, all part of the a larger deterministic scheme.

The upshot to all of this is that Fate of Atlantis’s story is fairly well written and well developed—much more so, than, say, the second film in the Indy franchise—but it is also essentially linear, like the story of a book or play. This is not interactive storytelling exactly, then, but it does include that ability to control the pace—that necessity of interacting at the sub-story level of items and puzzles—if one wants to move the plot forward… and so it is different from a book or play. There is an excitement and investment and a feeling of “being in the shoes” that one can’t quite get from non-interactive works.

… Spelunky

Spelunky, in contrast to FoA’s “plot points and story arc” approach, focuses on the smallest individual elements that make a story up, and how those elements relate to each other in general. It atomizes the story arc, and puts the resulting atoms in the player’s hands. The player is thus free to create their own story from scratch, using these predefined bits and pieces. The pieces are predefined mine you: archeologist explorer, whip, leap, spikes, bat, golden statue, booby trap, climbing gloves, monstrous spider, bomb, maiden in distress, rescued maiden, etc. But being so small, the fact that these elements are fairly limited and predefined still allows for a very wide (indeed, countless) number of combinations and interpolations. “Exit,” “leap,” and “maiden” come together to form: “The level exit is within sight. A careful downward leap will see both me and the blonde damsel I’m carrying in both arms to the next world.” “Spike,” “trap,” and “throw maiden” can become “She plummets downward like a rock, triggering the trap and taking an arrow point-blank to the face.” These sentences can then be strung together to form any number of paragraphs, like the ones we’ve already seen.

The surprising thing here is just how interesting Spelunky’s strung together stories can be. Sometimes they come out haphazard, to be sure, but other times you end up with arcs and plots whose exposition and climax and falling action are defined almost well enough to make Gustav Freytag proud. Indeed, the only time I’ve seen procedurally generated stories work this well is in The Sims, and Bay 12 Games’ Dwarf Fortress. What Spelunky does sometimes lack in terms of complex narrative structure and variety it attempts to make up for by extreme replayability.

Ultimately, despite their very different approaches, both Fate of Atlantis and Spelunky rely heavily on their stories in order to capture the player’s imagination. Think of story being stripped away from either game: in FoA we’d be left with a series of haphazard puzzles without much context, which frankly wouldn’t be very fun to solve. In Spelunky we’d be left with a similarly context-less series of button pushes… the resulting bits of gameplay and challenge might keep you mindlessly occupied for a small amount of time, but they would hardly create the compelling experience that is Spelunky.

Mechanics

As I’ve already mentioned, Fate of Atlantis and Spelunky are very different games, with very different mechanics. The interesting thing, though, is that if we step back a little and examine the skeletal form of each game, there are a number of mechanical similarities: we see that in each one the player controls a single character (at a time), which they move around the game world, and that the actions available to that character are very simple, and very limited. In Fate of Atlantis you can pick things up, look at them, use them together, give them to other people, talk to people using pre-written dialogue from which you choose. Spelunky lacks the conversational component, but otherwise the actions are similar: you can jump, whip, pick things up, throw, drop, and climb. In one game you use the mouse to do these things, while in the other you use a keyboard or gamepad.

The genre designations of “adventure game” and “action game” kick in when we consider that in Fate of Atlantis the pace is generally laidback, and quick movements aren’t required, whereas in Spelunky your survival often depends on your ability to manipulate your gamepad with speed and agility. In Fate of Atlantis you use the items you find to solve puzzles; in Spelunky you use items to enhance your player character’s capabilities, which makes defeating enemies and scaling cliffs easier.

Both games, though, defy their genres to some extent. Fate of Atlantis includes a dexterity-based fighting mechanism that is essential to one of the possible “game paths,” where you’ll spend much of your time in fist-fights with Nazis. There are also numerous story-critical mini games involving at least some dexterity, whether it’s driving a taxi through the streets of Monte Carlo, piloting a hot air balloon over the Sahara, or steering a Nazi submarine.

Some “adventure purists” may find these dexterity-driven activities to be a nuisance, but for others they will allow for a crucial connection to be established between themselves and their in-game character. The metaphor of “game button = fist,” “skill with controller = skill with blade” (or bow, or whip, or whatever) is a powerful one that games have used for a long time to lessen the disconnect between gamers and the characters they control. Skill with the controller becomes a surrogate for skills needed in a game world, which the player generally lacks. In this way a player can “feel” the difficulty inherent in bringing down a monster (or a Nazi), and “feel,” by extension, the skill that their in-game character possesses.

In Fate of Atlantis the little bits and pieces of dexterity-driven gameplay tend to be simplistic and sometimes cumbersome, but the attempt to blend genres is still noteworthy, and punching a Nazi time and again by smashing a button still manages to capture something of Indy’s character that clicking on a menu option with a mouse cannot.

Despite this attempt at innovation, FoA generally uses tried and true adventure gaming mechanics in tried and true ways. Spelunky, on the other hand, brilliantly blends simple mechanisms to create a very fresh gameplay experience. What looks like a typical platformer on the surface is, underneath, revealed to be a delicate blend of the best elements of two genres: the platformer, and the roguelike.

Roguelikes feature compelling exploration and superior replay value compared to other genres, but they tend to be lacking in their creation of mood and setting; they feature a nice tactical element, but you often lack a sense of immediate connection to the situation at hand because the dexterity needed by your in-game character is not mirrored in the way the game plays: encounters with monsters are equations on paper. By creating some wonderfully vibrant artwork, rotating the roguelike’s familiar top-down view by ninety degrees, and incorporating action-platformer elements, Yu manages to turn two genres on their heads and make each better for the effort. Spelunky is devilishly hard, but in just the way I’ve always felt a roguelike should be hard: the tactical and strategic elements are still there, but now your dexterity is worth something too, and the genre has acquired a new “here and now” urgency.

Ultimately, Spelunky’s golden crown is its procedural generation; I can’t think of any other platform game which implements this particular mechanic so extensively or so successfully (the levels are fresh, but always feel more crafted than random; they are challenging, but there is always a way through). This procedural generation makes Spelunky a much more dynamic game than Fate of Atlantis is. That is not to say that it is necessarily a better experience to play, but I think it does make it more ingenious, more groundbreaking, and perhaps more significant in the development of interactive storytelling and game design. (It could also be argued that, just as pixel art better suits the theme of archeological digging than polished 3D graphics, so procedural generation is better suited to telling a story of adventure and exploration than a linear plot arc is.)

In one of my favorite essays, Art as Play, Hans-Georg Gadamer makes the case that art is about play, imagination, creation, and the ability to do otherwise. I would say that the same is true for games. What sets computer games apart from other media is their interactive component: that component which allows the player to “do otherwise”; that ability to push a button and make an on-screen character jump, or speak, or go the other way. Fate of Atlantis obviously makes use of this interactive dimension, as we’ve seen, but that use is essentially limited to allowing the player to move a predetermined story forward. Spelunky, on the other hand, takes the same basic actions that the player of Atlantis is given, but with these actions allows the player to control their own story from start to finish—over and over again. The same story is never explored twice, and that question of “what if,” always lingers in the player’s mind.

Playing Spelunky is like opening up a writer’s toolbox and setting your pen to paper; but here, the story written is dependent not on your skill as a writer, nor on your limitless imagination, but on your ability to learn from and adapt to a particular game world. Here the story written is about choice and consequence, and skill. Here the story written will not be the story that you wrote, or the story that you read, but the story that you lived, in metaphor.

Meaning

The question that will naturally arise is, can a game like Spelunky say anything meaningful, with all its open-endedness, all the control it gives its players? This, really, is too big a topic to address in this small space: we are back to the most basic questions concerning the interactive medium, and the nature of art and toys and what makes them different.

Ultimately this is a question for another day, because neither Fate of Atlantis nor Spelunky will try to change your life with a profound message or soulful expression. These games, rather, are trying to capture a mood, a theme, an adventurous spirit: archeology, play, travel, and fun. Both games, in this regard, succeed very well.

What Spelunky has done, more than FoA, is show that a game can be interactive to the fullest extent and still achieve its goals regarding theme and immersion; show that a game can be nonlinear, and still create a story. Will other games be able to take this extreme level of interactivity and make you shout for joy, or cry from grief? I believe it’s possible, and Spelunky encourages me greatly; but we will, of course, have to wait and see.

Conclusion

Fate of Atlantis and Spelunky are both good games, and what both achieve at an abstract level is really quite similar: immersive worlds of adventure, action, archeology, and fun. Both do a commendable job of taking you to another time and place, and letting you live a story there. Fate of Atlantis achieves this feat through linear storytelling (with a couple of noted exceptions); like all classic graphical adventures, it distinguishes itself from film or literature by allowing (or forcing) the player to move the plot forward by solving story-integrated logic puzzles. It is a fine example of adventure gaming, and one that I would recommend to anyone wanting to play Indy from the comfort of their couch or desk: from the voice acting to the humor it is spot-on Indiana Jones.

Spelunky, at the elemental level, consists of many of the same components that make FoA up: pixel art, simple and straightforward mechanics, basic player actions… by contrast to FoA’s fairly genre-hugging form though, Spelunky has shown us a new way to make a game: a new way to put together old mechanics to achieve something imaginative and fresh. With its bold use of procedural generation Spelunky has pushed the boundaries of interactive storytelling, of platform games, and of game design in general. It is playful, imaginative, and full of possibility: in many ways a prime example of what all games should be.

Further Reading

- A nice review of Spelunky by Anthony Burch, for The Escapist.

- Another review of Spelunky, this time by Darren Zenkofor, for Vue Weekly.

- The official Spelunky thread at TIGForums, where you can learn all about the development of this awesome game.

- Even Dickens, fearless editor of adventuregamers.com, explains in brief why Fate of Atlantis is one of the top 10 adventure games of all time.

- A good long review of Fate of Atlantis at The International House of Mojo.

- A review of Fate of Atlantis by Peter Lamberton for Adventure Classic Gaming.

- An interview with Bill Eaken, lead artist for Fate of Atlantis.