Formalism is another strong suit for video games, especially if we go with criteria like those of Richard Eldridge, who suggests that “what makes something art is the ‘satisfying appropriateness’ of its form to its content” (NR 239), without passing any judgment on the relevancy of that content. While the commercial sector of video game production often limits its aesthetic style to cutting edge photo-realism, and the cinematic techniques of film (we’ll call that “Cinematic Formalism”), there is a vast array of formally sound stylizing to be found in smaller, independent video game production. Besides Cinematic Formalism, we have distinct examples of what I will call Retro Formalism, Abstract/Minimalist Formalism, and Psychedelic Formalism.

Retro Formalism has to do with creating art within the bounds of retro video game design: storytelling within the confines of the platform or side-scrolling genres, visual representation limited to pixel-art. The form and content of many retrograde games is balanced extremely well, and, as Tilman Baumgärtel points out in “On a Number of Aspects of Artistic Computer Games,” pixel art is a historically-grounded and significant art form in itself:

The “building-block look” of the first games for video arcades or early play consoles like the Atari 2600 actually recall historical techniques of picture-making in stunning ways. Ancient Greek and Roman mosaics or the Moorish “alicatado” (tile covering) of the Alhambra in Granada are only two examples of historical production methods that show a clear connection to the pixels from which computer images are constructed. In the meantime, the fact that early games of the seventies have an obvious connection to abstract art of past eras has almost become a commonplace in academic discussions.

Machination’s 1995 release Framed, and Blackeye Software’s Eternal Daughter (2002), are two examples of games that do a superlative job of uniting their storytelling, gameplay, and visual art elements within the bounds of traditional video game limitations—in the case of Eternal Daughter, very deliberately applied limitations. Older classics like Metroid, Super Mario Bros., and The Legend of Zelda need hardly be mentioned.

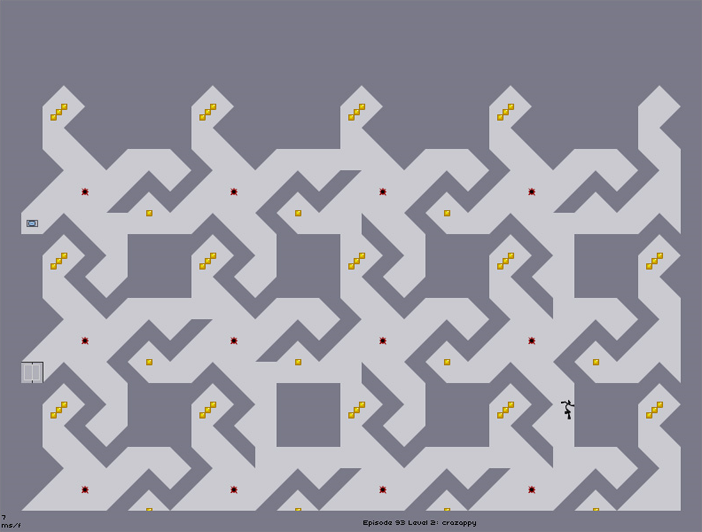

Minimalism is another aesthetic style which is currently receiving heavy treatment by a certain sector of independent game developers. Duo-tone color, vector line graphics, and ultra-simple controls are some qualities that characterize these games. The focus is not so much on working within limitations specific to older video games, or using pixel artwork, so much as it is on re-imagining what minimalism within video games could look like, while drawing heavily from the tradition as already established in visual art.

A good example of a Minimalist video game released recently is N by Metanet Software. N is a Lode Runner spin-off stripped of everything but its bear essentials, where the focus is brought down to the elegant movement of the player-controlled ninja, and his interaction with the simple shapes which span the playfield. Metanet (run by a filmmaker and a painter) very deliberately incorporates Minimalism and aesthetic principles into their design (as confessed in multiple interviews), and the results are very good; not only does N look stunningly elegant, but it has been universally praised for its similarly elegant gameplay. Even N’s name was chosen deliberately: “We just wanted something simple that matched the aesthetic of the game. ‘Super Jumpy Ninja Dude!’ would ruin the grace and elegance” (State interview).

Vib Ribbon and The Line are two games that take a minimalist approach even starker than N’s, creating environments that make you feel like you’ve just stepped into a painting by Barnett Newman or Frank Stella. Or we have The Crimson Room by Toshimitsu Takagi, a claustrophobic adventure brought down to lines and color, and a click of the mouse.

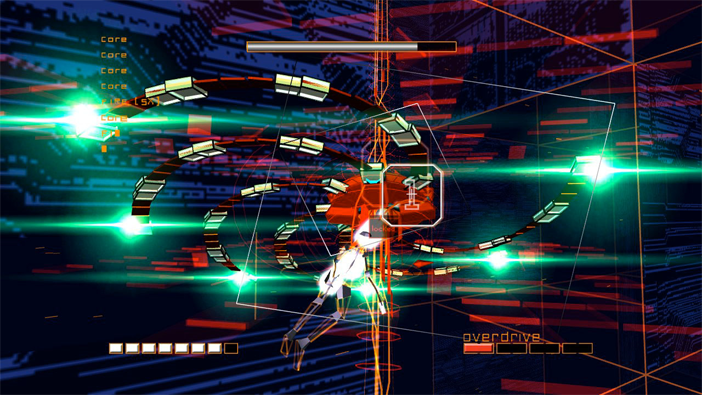

Finally, we have “Psychedelic Formalism,” a term I use to describe the chaotic and complex formal unity created by games like Rez, Spheres of Chaos, Mutant Storm, Darwinia, and Kenta Cho’s shooters. These games swirl and dance and scream, and spray colors and sounds like fireworks. The colors are bright and beautiful and balanced, and the chaos is formally stable: this feels like the formalism of science fiction, of the future, of electrons racing across my motherboard… of the underpinnings of video games themselves—what better unity could we ask for from this medium?

So far our discussion of Formalism has been restricted mainly to the visual, and the reason for this is that we know how to tread that ground. But as we are talking about video games, I think more significant than formalism within their visual presentation is formalism which includes their interactive element, includes their gameplay. As David Hayward points out in “Video Game Aesthetics: The Future,” “the aesthetics of games are not merely to do with HUD and menu graphics, but are about the way in which game worlds are presented… interactivity is more fundamental to the medium than most if not all other parts of it.”

Formalism, as Greenberg has pointed out, is not really about balance within one particular given sphere (like visual appearance), but rather about using the unique qualities of a particular medium to understand that medium: about balancing what the medium has to offer with what the medium is doing—about balancing content and form. Says Greenberg:

The unique and proper area of competence of each art coincides with all that is unique in the nature of its medium… Although the Old Masters are indeed great art, their greatness lies not in their representational qualities or their realism, but in their formal qualities, the qualities that are specific to the medium of painting itself (NR 110).

What is the quality specific to the medium of video games? Interactivity; and I think each of the games mentioned above manages very well to unify its interactivity with its content—to elegantly bind the user’s interaction with the user’s goal within each game. If we’re going to be strict formalists then that’s enough to make these video games work as art—because content in itself no longer matters: only equilibrium of content and form. Of course, those who do not find formalism to be sustaining with regards to painting or sculpture will not likely find it to be sustaining here.