Don Postema, Professor of Philosophy at Bethel University says, “Art in the last 100 years has not been about the aesthetic… it has been about thoughts, ideas.” Take a look at Duchamp’s In Advance of a Broken Arm or Rauschenberg’s Odalisk or Craig-Martin’s An Oak Tree and it’s easy to see Postema’s point. Art is on its way to being consumed by philosophy, and currently that means the ideas of Foucault, Derrida, Rorty and other postmodern thinkers: deconstruction is the game. How and why do we see things the way we do?

It turns out that deconstruction is a large part of the focus of the new genre of video games called “art games.”

Art games are decidedly noncommercial in that they function primarily as single-use, or even disposable experiences due to their limited playability. Unlike Grand Theft Auto III or Final Fantasy X, popular games produced by hordes of developers that require weeks to master, art games tend to be more limited in scope. Typically, retro-styled art games do not offer players hours of play possibilities, rather, they provide viewers with a simple interface that assumes the viewer’s familiarity with game play in arcade classics such as Defender, and Pitfall. In the art game, wry social commentary sparks interest rather than grandiose landscapes and multi-nodal navigation (Holmes 47).

One such art game is Thomson and Craighead’s Trigger Happy, a retro Space Invaders clone that has you shooting down not alien invaders, but words from Foucault’s essay “What is an Author?”

“In bombing the phrases, the player metaphorically deconstructs Foucault’s text which itself deconstructs the idea of the author,” notes Holmes. Just how much deconstruction is allowed?

Left to My Own Devices, a game by Geoffrey Thomas deconstructs the very idea of gameplay. Here players really are left to their own devices as they explore a narrative of loss and renewal gradually revealed through fragmented game segments which almost seem broken—like the central character that you play.

Jodi’s SOD, and UWM’s NPRQuake are two examples of deconstructionist “mods,” alteration packs made by independent developers which modify commercially available video games in certain ways. Both of these mods alter id Software’s popular 3D shooter, Quake.

Jodi has subjected the game Quake to a radical treatment, resulting in all objective details and all textures being removed, with only abstract symbols remaining. This precursor of Quake, which was also developed by id Software, is now reduced to just a mysterious black and white landscape in which only rarely can be seen what is being hunted or what is blocking the way. The castle with the intertwined passageways, through which the player has to find his way, looks like a gallery in which only copies of Kasimir Malevitch’s “Black Square” are hanging on the walls; Nazis have become black triangles—they are recognizable because they occasionally yell “Achtung!” Of all the game modifications that Jodi has produced, it is the graphical aspects that are the most reduced. At the same time however, the mechanics of play of the original game are respected (Baumgärtel 8).

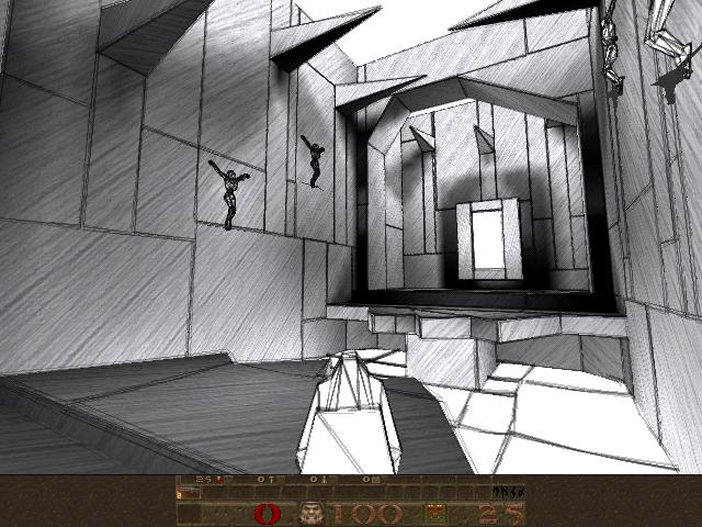

NPRQuake does similar things, taking the 3D environments of Quake and rendering them as if they were hand drawn by a pencil and paper artist, a blueprint maker, or a painter. “If you have ever imagined running around inside a painting or a drawing,” state the authors, “you are beginning to get the idea.”

SOD and NPRQuake raise questions about the nature of art and of video games. Where is the game actually defined if we can strip away its visuals and still use its mechanics? When do video games become video games, and how much do we have to take away before they are no longer video games? What is the relationship between 2-dimentional and 3-dimentional rendering? How do we think about the structure of video games? Who are the authors of modded video games? When does violence become violence—when a triangle becomes a Nazi?

Cory Arcangel, creator of Super Mario Clouds takes video game deconstruction to the extreme by hacking a Super Mario game cartridge (hardware, not software) so that when played, our protagonist Mario disappears along with all the obstacles in the game: all that remain are a few fluffy white clouds in a light blue sky. Gone are “the narrative elements of the game and everything that made it dynamic” (Baumgärtel 10).

Finally, a very interesting type of video game deconstruction—or reconstruction—takes the form of what Baumgärtel calls the “rematerialization of immaterial processes” in games like Geissler and Sann’s Shooter, Olaf Val’s swingUp, and SF Invader’s Space Invader. These games, which can hardly be called video games any longer, take the virtual world of their computerized counterparts and recreate or embellish them in material ways. Suddenly we have to ask, where is the virtual space, where is reality, and where is the game?