Daniel, the protagonist of Exit Fate, is a soft-spoken orphan who fights only so that peace would eventually soothe the troubled land. He is separated from his army during a night raid, eventually finding himself at the head of a new army while searching for clues about his cursed fate and how to exit it. He meets over seventy heroes of all shapes and colors such as Meiko, a girl-scout with a mighty pen and a mightier right foot who you can assign to interview the other characters for more backstory, or Klaus, the last of a noble line of talking cats who deigns you worthy of his time after you provide him a room furnished as those of your best generals. You can freely select your adventuring party from among these heroes, although besides fighting, some heroes will help run your magic shop, smith your weapons, or even change your color settings. Occasionally, there will be a wargame-style square-grid mission involving the entire army’s special abilities.

Right, it is just Suikoden II; or as critics would say, any other Japanese RPG. Aren’t those all the same?

Ripoffs and Homages

The biggest battle Exit Fate has to fight is convincing its players that it is not a ripoff. Initial impressions don’t help its cause, for Exit Fate uses too-familiar Suikoden II audio everywhere from the dungeon themes to the vaguely-oriental chime that sounds every time you recruit a new character 1. Furthermore, as Xander points out in this post (which almost stopped me from playing the game), the introductory sequence of Daniel blacking out after a night raid and a battle with a mist monster at the end of a pass are lifted straight out of Suikoden II.

It seems like an open-and-close case, one with the Suikoden II disc in it. However, there is much more to Exit Fate.

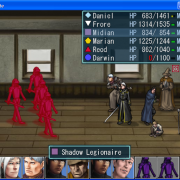

For battles, SCF borrows the row-based 6-person setup from Suikoden, but this is just a skeleton for a fresh battle system. The 3x3 grid (like Megaman Battle Network) gives more planning involved than the simple “strong characters in the front, weak ones in the back” needed for a 2x3 grid in Suikoden, especially with most special abilities having very specific targeting ranges. For example, ice spells and spears hit entire columns while lightning spells hit a center tile and the (up-to-four) adjacent tiles. The magic system is more daringly different, with all party members sharing the same spell pool and MP recharging automatically over time. My favorite feature is that the bottom of the screen displays the order of action of every agent in the battle, rewarding planning several turns ahead. Thinking, by the way, is actually necessary in this jRPG, unlike most of its brethren where almost every battle can be won by tapping a single button.

For battles, SCF borrows the row-based 6-person setup from Suikoden, but this is just a skeleton for a fresh battle system. The 3x3 grid (like Megaman Battle Network) gives more planning involved than the simple “strong characters in the front, weak ones in the back” needed for a 2x3 grid in Suikoden, especially with most special abilities having very specific targeting ranges. For example, ice spells and spears hit entire columns while lightning spells hit a center tile and the (up-to-four) adjacent tiles. The magic system is more daringly different, with all party members sharing the same spell pool and MP recharging automatically over time. My favorite feature is that the bottom of the screen displays the order of action of every agent in the battle, rewarding planning several turns ahead. Thinking, by the way, is actually necessary in this jRPG, unlike most of its brethren where almost every battle can be won by tapping a single button.

For plot elements, I won’t give any spoilers, but from the outcomes of many similar situations as Suikoden II it is clear that SCF borrowed them for a reason, leading me to strongly believe that the mist monster incident was only to set a frame to prime your expectations. In fact, SCF did exactly this in Last Scenario, where he made the first portion of the game a blatant cliché as a foil for his later twists2. SCF was privy to what the average jRPG know-it-all player like me is expecting, as many times I had to laugh at myself for being wrong after making strong assumptions about what would happen next. As a fifth-rate armchair strategist, I am also very impressed by the care put into the political and military maneuvering, which is decidedly better than those in every jRPG I have seen — while the strategical motives behind certain actions are questionable if not unrealistic, there are a few tactical ones that are at least as sophisticated as those of many popular novels, in particular Shui Hu Zhuan, the Chinese historical novel which inspired the Suikoden series. This is thanks mainly to Bast, the lead strategist of Exit Fate’s world, whose wisdom is both mature and concrete (a rarity in jRPGs), if not quotable.

For characters, SCF keeps the feel of jRPGs by having a cast so diverse as to be tongue-in-cheek: your thieves, rangers, and paladins fight next to ninjas, scientists, and even a guitarist. Creating unique and memorable characters has been an undisputed strength of the genre, so much that true innovation may be logically impossible, but SCF still has found ways to challenge jRPG tradition. For one, unlike the protagonists of Suikoden II and most other jRPGs, Daniel talks. Like most everyman-type TV leads, he has a decidedly “average” personality, with an ego not particularly humble or arrogant and a demeanor not particularly shy or confident. Though just from being able to express himself, he blows away any Cloud or Squall that may be brewing on the horizon. My main satisfaction, however, comes from the portrayal of female characters. Traditionally, they’re delegated to healers and mages and exploited to wear extremely impractical garb. The clothing usually complements perfect curves and youthful faces, as if the auditions for female jRPG roles require both unnatural skill and good looks, kind of unfair when men can just get away with the former. The women in Exit Fate can axe it up with the best of men, have much more realistically distributed faces, and most surprisingly, wear functional clothing over physically feasible proportions.

I’m not going to dodge the music issue, which seem to account for around 80% of the criticism for Exit Fate. I am entirely sympathetic to SCF’s choice of music tracks because they were very appropriately chosen, especially to experienced jRPG players who have heard them before and have associated with them very specific sentiments, exactly the same reason that the same classical pieces appear again and again in film. Also, SCF is a one-man team and doesn’t have a music squad; while he indeed could have just gotten “open source” music elsewhere, I much prefer him picking the perfect track he had in mind for each occasion and just citing the source, as he did, rather than scrounging up unfamiliar and possibly less fitting music just to look “original” - besides, the two situations are equally unoriginal as neither would involve SCF’s own music.

And where did the time he “saved” with his music go? The meticulous tinkering in the other aspects of Exit Fate shows only a dedicated effort to improve upon not only Suikoden II, but the trappings of the entire jRPG genre.

And where did the time he “saved” with his music go? The meticulous tinkering in the other aspects of Exit Fate shows only a dedicated effort to improve upon not only Suikoden II, but the trappings of the entire jRPG genre.

- The most obvious proof of love is the completely original character art, with careful attention to detail in around ninety portraits. The style gives a fresh feeling to a genre dominated by mainstream-anime aesthetics. While I do love certain anime-inspired art, sometimes it feels like every jRPG character looks like an Asian teen whose parents give unreasonably generous fashion allowances.

- The oft-praised tactical battles in Suikoden II were, in general, very easy and often scripted. This meant that I remember them more as part of the cinema than as a true minigame, but in Exit Fate they’re much more integral: the maps are bigger, the battles are more challenging, and there is even an option (once you recruit the right hero, of course) to re-play battles and to play bonus battles.

- Besides the sharply logarithmic experience system3, Exit Fate has a very clean design that allows you to escape (via bribery) every random encounter with a single button. These two features discourage grinding and make dungeon-traveling faster, ameliorating two big nuisances that have plagued jRPGs.

- Finally, SCF has a sense of humor that surfaces just enough to not clash with setting the mood for a story with serious themes. A couple of townsfolk reprimand you for barging into people’s homes and taking their treasure, and one NPC comments to another that his impossibly big sword is a sign of overcompensation. This is in cute contrast with Daniel, who thankfully has a normal-sized sword even though he resembles a less-Asian Sephiroth.

Maybe this is the difference between a homage and a ripoff — a homage will take ideas, themes, or even exact replicas and put them in the open while earnestly filling in the rest in loving if not slightly fresh ways; a ripoff will pretend to be different from the source material but have no soul of its own. To use another analogy, the homage struggles upwards but signals to the cameraman to lower the lenses so the shoulders of giants are in the shot, while the ripoff, content with mediocrity, will look down to make sure it is on top of the giants, all the while trying to push them out of the picture. Exit Fate is decidedly a homage.

“So What? The Genre Sucks Anyway.”

Savvy readers will realize that I loaded my review by giving almost as much criticism to jRPGs in general as giving praise to Exit Fate. This is mainly so I can bridge into a question that I think is much more important for jRPG players (like myself): What if the genre itself is not worth playing, as the (amazingly keen) article Awesome by Proxy seems to imply?

Well, after having played way too many of them, I’ll just admit it. Yes. jRPGs suck.

I personally justify playing most games because they exercise some skill, be it reflexes, tactical thinking, or pattern recognition. As I am both easily amused and easily pleased, this is enough reason for me to pour entire days of my life into Garou: Rise of the Wolves or Rise of Nations, much like we would justify playing chess, poker, or baseball. Sadly, the skill component in jRPGs is basically nonexistent4.

“But the strengths of jRPGs lie in plot!” is one of those oft-used retorts that really don’t have much substance. If any videogame, jRPGs included, really had as good a plot as the boxes pretend they do (my Odin Sphere box boasts “worthy of a place in the canon of classic literature”), that argument would be settled by now. Yes, occasionally twists “ooh” us and betrayals “ahh” us – but these thrills do not equate a good plot by themselves. By “good plot,” I think most jRPG players actually mean “good character development.” This is more convincing; games have great potential here, because of the medium-exclusive interactivity that can really tie our hearts to characters. When this is done well, when we’re forced to smile or cry simply because some pixels are moving on the screen, jRPGs triumph, like they did for me in the opera and solitary island scenes in Final Fantasy VI. Unfortunately, most jRPG (or videogames in general, actually) character development is predictable because of the limited library of human experiences (strangely, they all seem to be related to fighting) that jRPGs borrow from. As such, we’re frequently reduced to a few character archetypes, and there are only so many things you can do with them: the cold, burly tank will always be warm to his secret little sister, or the evil villain was mistreated as a child and is the main character’s brother, or at least they are brothers in the sense that they are clones… while jRPGs have made steps, they’re nowhere near running.

Forget the whole “finding Citizen Kane of video games” bit for now (there are too many worms in that can). The biggest problem about making “mature” jRPGs is market demand — jRPGs tend to be mainly written for semi-literate children/young adults with a love for escapism. Now, there is nothing wrong with being in this demographic (I try to be one as best as my age permits), but most of the consumers are used to a culture of mainstream anime/manga with particular types of character designs and dialogue. While I firmly believe both children’s writing and anime culture can be mature and thought-provoking, as anyone who has read The Little Prince or Monster would agree, the problem here is economic: these younger consumers are less picky with their product; as anyone who has watched lots of cartoons as a child can attest, when we are younger, we really did not mind being fed the same characters, dialogue, and plots day after day after day. these conditions stifle the potential of jRPGs by providing little financial incentive for improvement. Most visibly, this shows in the language, which tends to fall under one of two types: children talking (either in bodies of children or adults) or an unrealistic, negative stereotype of “adult speak.”

I am now literally afraid to start new jRPGs –- the truth is that I’ve resorted to reading Let’s Plays of most jRPGs instead of actually playing them. Why don’t I just start each one and stop when I realize I don’t like it? Think about those times when you had to finish the bad movie or the 7-season TV series; you were “invested.” Video games only make this sentiment stronger because that very interactivity we treasure so much creates a more binding “investment,” because these are, after all, our heroes and our adventures. For people with addictive genetic dispositions, like me, many video games become harmful drugs instead of innocent pastime. This means long game lengths are the real poison — jRPGs nowadays take no less than 50 to 100 hours to complete (to put it in perspective, the entire run of Friends is somewhere around there)5.

So what is left?

After giving all this criticism, why do I (and many others) keep coming back to jRPGs?

Sometimes, I perversely feel that we’re lucky to have Sturgeon’s Law, because it gives us some meaning in the search for that other 10%. The talented “Pitchfork” Pat seemed to have only really liked a couple out of the last twelve not-very-Final Fantasies in his amazing anthology, although he clearly took his time to play every one of them to write his epic heart-filled reviews. For me, the few times I didn’t regret playing jRPGs (Final Fantasy VI, Chrono Trigger, etc.) made up for the many times I did. I suspect Pat feels the same. For all the flaws of jRPGs I’ve pointed out, the genre still needs to exist, because like all its brothers from FPSs to racing, it fulfills a particular potential of the medium of videogaming, accenting a particular type of presentation on the screen while attracting a particular personality in a gamer. I honestly feel that the greatest problem the jRPG faces as a genre is due to its definition: its most visible aspects are the aspects of books and movies.

Let me expound. Even people who disdain FPSs know that they’re missing out on a particular kind of wish-fulfillment that other media cannot replace. However, it may be entirely unclear to most people that they are missing out on anything at all by not playing jRPGs; after all, they’re just linear stories. Movies have been doing linear stories for about a hundred years (and books a whole lot longer). This is really the real “weakness” of jRPGs. We’re always going to hold them to higher standards, comparing their prose to Homer and their pacing to Hitchcock while FPSs are scrutinized by having their engines compared to Half-Life 2, which is not even a decade old. In a thought experiment world where books and movies don’t exist but games do, the jRPG genre would be rightly honored for their writing because of this alone.

Of course (and extremely lucky for us), this is not our world. The primary mistake we’re making in this “games vs. books/movies” battle is making it a battle in the first place, like some pathetic struggle for legitimacy. However, if we insist on fighting, games must evolve through innovation. This is where indie games, like Exit Fate, come in: here, we can make homages and parodies out of love, trying a lot of things mainstream jRPGs don’t or won’t. SCF’s art, in particular, would never appear in a mainstream jRPG because the eyes are too small and the jaws too angular. Strong indie scenes are exactly why great games are still coming out of the interactive fiction and adventure genres, two classes of games whose measuring sticks are sometimes even closer to books than those of jRPGs. They barely even have retail markets, but those games continue to evolve for the better thanks to the nurturing of caring communities.

This is why things like ASCII’s RPG Maker Series, like its cousins for more general game-making Game Maker, KnK, and Flash, empower videogames. Yes, they introduce some noise, even trash, but they really do let creative, talented individuals translate their dreams into bytes without big teams, development schedules, or three years of C++ experience. The indies gave us classics like the irreverent Three the Hard Way, artistic experiments like the non-violent Sunset over Imadahl, poignant parodies like Barkley’s Shut Up and Jam (which, by the way, was not made with RPG Maker).

And thankfully, they gave us great homages like Exit Fate.

Not only do great homages help jaded players recall why we loved these games so much, they also set higher standards for the community; those higher standards produce a demand for raising rusty bars. Yes, jRPGs are cursed by their design to have to prove themselves with harsher standards. But their fate does not lie in mediocrity, as long as there is enough love to keep making them.

So, while jRPGs suck,

… so do most videogames. Or most movies. And that’s why we search, for that good jRPG. For that good videogame. For that necessary videogame.

-YZ

Resources

Further Reading

- If you only had time to play one game but get the feel of the Suikoden series (and you really should), Exit Fate would do nicely. The obvious other option would be Suikoden II, the series fan favorite, which still remains one of the most loved jRPGs of all time, if not just for the best boss battle in jRPG history (warning: spoilers). As usual, Hardcore Gaming 101 has a good article on the Suikoden series here.

- As a videogame advocate, I feel we players are obligated to also consider the negative points of videogames and consider how they affect our own personal lives, otherwise we would be no better than blind zealots. One of my favorite articles of the year keenly illuminates some weaknesses of jRPGs and what they say about the player. It extends to some great points about gaming in general and even how people find meaning in life, but in a very concrete and readable way. Strongly recommended: Awesome by Proxy.