I’d like to share with you today a few games that were made in two hours each. You read that right. Two Hours each. But why on earth would I do such a thing? Can a game that’s made in two hours possibly be worth playing, much less writing about and encouraging others to play? My short answer is of course yes, and the reason is this: some games can only be made in two hours.

What do I mean? I mean that some games, if they are to be good games, require weeks, or months, or years of effort and dedication to produce (granted, I haven’t actually played many games that have taken years to produce that I would actually consider very good, but you know, it’s a theory: we can perhaps imagine an inspiring triple-A title). Other games require not to have that time, because there is nothing for them to do with it. I’ve used the novel/haiku/sentence analogy before, and I’ll use it again: some games are analogous to novels in their scope and their ambition, while other games are more akin to short poems, sentences, or even singular words. We need these shorter games, just as we need the longer ones because, as Ian Bogost expressed two years ago in an article he wrote for Gamasutra, we need games of every shape and every form, expressing every kind of thing.

This is the spirit of Klik of the Month Klub, a power-to-the-people, once-a-month online gathering that’s about individuals seizing their creativity, seizing the inspiration of the moment, and making a game in two hours. The results are everything from here to there, most of them “glorious trainwrecks,” but all dripping with individuality and expression, as far away from corporate clones as you can imagine. One faithful KotMK attendee is Anna Anthropy (aka dessgeega, auntie pixelantie), thoughtful games critic and “pixel provocateur,” and it’s her games I’d like to share with you today.

The games I’m going to discuss can be found in Anthropy’s recently released “Shootin’ Starcade,” which presents six games in one tasty package. There are spoilers throughout the following reviews, so if you want the virgin experience play the games first.

Space Escapers

One of two games designed for two players on one keyboard, in Space Escapers one player uses the arrow keys to help space invader P.O.W.’s escape, while the other controls an on-rails prison guard via the mouse, and attempts to shoot the escaping invaders. This game is wonderful for multiple reasons.

One of two games designed for two players on one keyboard, in Space Escapers one player uses the arrow keys to help space invader P.O.W.’s escape, while the other controls an on-rails prison guard via the mouse, and attempts to shoot the escaping invaders. This game is wonderful for multiple reasons.

First, it turns the classic space invaders game on its head in an obvious but nicely formal way: not only are the space invaders helpless and trying to escape (as opposed to powerful and invading), but they enter play from the bottom of the screen, while the prison guard patrols across the top, turning the game upside-down both metaphorically and literally.

Second, the game is wonderful in the way it pits its players against each other. Instead of the cooperative or well-balanced versus gameplay you would typically find in multiplayer-on-one-keyboard games, we have here a massively unbalanced scenario: to escape the prison camp each space invader must make three passes across the screen, an endeavor which proves impossible unless the prison guard is napping, or decides to let you escape. The fact that each player is represented by a different piece of hardware just puts the cherry on the cake of this peculiar match-up.

Bibleshock

Bibleshock is “a game of difficult and slippery moral choices and their consequences.” Actually, it’s a game about how game developers make games about difficult and slippery moral choices and their consequences. The game presents the player with a series of situations in random order, always posing the question, “What do you do?” In each situation you have exactly two options to choose from.

Bibleshock is “a game of difficult and slippery moral choices and their consequences.” Actually, it’s a game about how game developers make games about difficult and slippery moral choices and their consequences. The game presents the player with a series of situations in random order, always posing the question, “What do you do?” In each situation you have exactly two options to choose from.

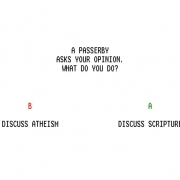

For example, you “Encounter a hooker,” and can B) “Hire her and kill her,” or A) “Talk to her and listen to her.” Or you “Encounter an individual who opposes constitutional ideals”: B) “Quote Marx,” or A) “Quote founding fathers.” Or, one of my favorites: “A passerby asks your opinion, what do you do?” B) “Discuss atheism,” or A) “Discuss scripture.”

In each of these situations answer B is on the left, below a red “B”, and answer A is on the right below a green “A.” Choosing options B predictably lead to things like corruption, becoming communist, and the destruction of the world, while options A bring peace, freedom, and salvation.

The interesting thing about this game is the fact that the patent notice on the opening screen is not in jest: the game is actually based on the first part of a 119-page patent application submitted January 15, 2009 by a Dr. Elliot McGucken; the application is for a “System and method for creating exalted video games and virtual realities wherein ideas have consequences.” Read through the abstract (and skim the other 118 pages) and you’ll see that McGucken appears to be entirely serious.

We can all have a good laugh at McGucken, but the real weight of the game lies in its ability to bring home this realization: we are McGucken. The way we build morality into our games is pathetic, shallow, and entirely useless. We get excited by efforts like Fable and Bioshock (and I’m not writing those games off completely) when they are nothing more than McGucken++. Can we hear ourselves already? What he said. And he said.

Gay Sniper

I love how this game confused me. From the screenshot (and the name) I was sure Anthropy was going to make some point by having me snipe gay people. A bit cliché, I thought, but let’s see where it goes. As the game started and the audio from a “West Virginia for Marriage” ad started playing, talking about heterosexual marriage as the foundation of our society, and how it’s under attack, my assumption only solidified. I started moving my sniper scope around (the screen is black, except for your crosshair), searching for the homosexual couple hiding somewhere on the screen.

I love how this game confused me. From the screenshot (and the name) I was sure Anthropy was going to make some point by having me snipe gay people. A bit cliché, I thought, but let’s see where it goes. As the game started and the audio from a “West Virginia for Marriage” ad started playing, talking about heterosexual marriage as the foundation of our society, and how it’s under attack, my assumption only solidified. I started moving my sniper scope around (the screen is black, except for your crosshair), searching for the homosexual couple hiding somewhere on the screen.

But I couldn’t find them anywhere. Only what appeared to be the image of a happy heterosexual family blowing bubbles together, as every happy, heterosexual family does. Is one of these people secretly gay? I wondered. Oh well, let’s see what happens. I aimed at the father, and pulled the trigger. An image of a shattered America appeared, and the text, “America is destroyed.”

I am sure it has become obvious to my reader, but it was only then that it dawned on me: I am a sniper who is gay. I am the one attacking America.

What’s great here is the inversion, again, of the expected: by making the player a sniper who is gay, instead of a sniper of gay people, Anthropy turns from the clichéd “how terrible is it to snipe gay people,” to the absurdity of the claim that gay people are destroying the family and bringing down America. The really wonderful (or disturbing) final piece here is that the “West Virginia for Marriage” ad that the game was inspired by actually shows a happy family with a sniper crosshair moving over them, as a man’s voice proclaims that same sex marriage is “a closer reality than you may think.” Watch out for gay snipers.

Dodgeball

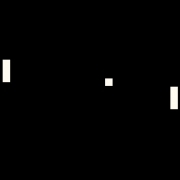

Dodgeball is the other two-player game in this mix. It is an inversion of one of the first videogames ever, and it’s a nice inversion. Each player controls a paddle, and instead of bouncing a ball back and forth, you try to dodge a ball that bounces off the walls (and gains speed with each bounce). Letting the ball hit your paddle means losing a life, except that you can safelycontact the ball when it is behind your paddle, so that you can “dribble” it a bit before shooting it back in your opponent’s direction.

Dodgeball is the other two-player game in this mix. It is an inversion of one of the first videogames ever, and it’s a nice inversion. Each player controls a paddle, and instead of bouncing a ball back and forth, you try to dodge a ball that bounces off the walls (and gains speed with each bounce). Letting the ball hit your paddle means losing a life, except that you can safelycontact the ball when it is behind your paddle, so that you can “dribble” it a bit before shooting it back in your opponent’s direction.

The game looks exactly like Pong, and controls exactly like Pong. As such, I sometimes found myself forgetting that I was not actually playing Pong. This was a problem, because the game obviously scores in exactly the opposite way of Pong, so that saving your life in Pong means losing your life in Dodgeball, and vice-versa. And this is what makes the inversion interesting: this interplay of appearance, expectation, and reality—and the human player on the other side of the room. If Pong is sex, then Dodgeball, I suppose… is also sex. Sex in a different position, or with a different partner, or upside-down in another universe. Or wait—maybe Dodgeball is abstinence…

Adventured Servants

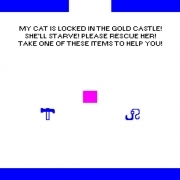

Adventured Servants is a game about frustration with games. It is, I think, as fine a game about frustration with games as I have ever played. The premise is very simple and very clear: you must rescue a cat that is trapped in a gold castle, and you can choose one of two tools to help you do so: a hammer, or a hook on a string. You sense, as the game starts, that you are being trapped—the game screams at you to run away. And yet, before you know it, you have chosen one of the instruments, and it is too late. You can no longer put it down, because that cat is depending on you, and you are the only one with that bloody hook on a string.

Adventured Servants is a game about frustration with games. It is, I think, as fine a game about frustration with games as I have ever played. The premise is very simple and very clear: you must rescue a cat that is trapped in a gold castle, and you can choose one of two tools to help you do so: a hammer, or a hook on a string. You sense, as the game starts, that you are being trapped—the game screams at you to run away. And yet, before you know it, you have chosen one of the instruments, and it is too late. You can no longer put it down, because that cat is depending on you, and you are the only one with that bloody hook on a string.

The visual presentation is taken straight from the classic Atari 2600 game Adventure, but is no less effective for that. Your player character is a square, and the world around you is empty save for rectangles of color which form rooms and mazes and hallways and spaces. So simple, yet so perfectly applied: as in Adventure, playing the game feels like walking through one of Mondrian’s paintings[1]. What better style for a game that questions gameplay, for an abstract game that is also a commentary?

There are many dead ends, and many false starts, and eventually, if you persist, you will find the “castle” with its imprisoned cat. If you chose for your tool the hook on a string, you will be met with the message you knew was coming:

The gate is locked, but has a small window. If you had a hammer you could break the window and unlock the gate.

Of course there is no need to go back, because you know that the cat is doomed. That gaming is doomed. That you are doomed, because you are adventured.

The Sentence

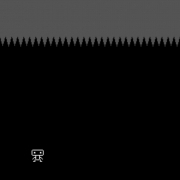

The Sentence is “a game about an advancing wall of doom.” Inevitability.

The Sentence is “a game about an advancing wall of doom.” Inevitability.

“You have been sentenced to death,” we are told, as the game opens. We are then presented with our player character, a “little hopping dude,” and an advancing wall of doom: a gray curtain of spikes, falling slowly from the ceiling. The nice thing here is the precise level of control the player is given: you are not completely unable to move, you are not forced to watch and do nothing at all—you can run, you can jump and make boing-y sounds. But you can’t go off the screen, and you can’t do anything about that wall. Everything is so stark and abstracted, that it’s a beautiful little metaphor.

The abstraction, combined with the time you have to wait, makes you wonder: is that really a falling wall of spikes? Am I really going to die? Or have I been lied to? Maybe that wall is a harmless curtain and I’ve just finished giving a speech; maybe I’m dreaming and upside down, and diving into the ocean; maybe I’m already dead, and floating up to heaven, and what I’m seeing is a line of pine trees against the gray morning sky; maybe that’s my mother ship.

The thing becomes a micro-dream, a hallucination. And then it’s over. All that’s left is a splatter of red against a perfectly gray background. And the dream goes on.

[edited Jan. 4, 2010]

Conclusion

I started this article by saying that some games can only be made in two hours, and that’s what I’m going to maintain. You could take the core idea from one of the games above and expand it, and add 3D visuals, and chuckle at your cleverness, but you would be making a different game and a different kind of game; probably, it would be silly. These games are not 3D games, they are not long games, they are not games to tell you a complicated story; rather, they are short, small, to the point, and meant to be that way. They are not grand visions that are pieced together by hundreds of people over months or years—they are another kind of expression: creative flares, sparks of individuality from another person out there. That is why I like them, that is why they are needed, that is why you should play them, and that is why you should get up off your seat and make your own.

Resources

I’m serious when I say you should make games: spend two hours of your life throwing a game together, and you’ll be a better person for it. Don’t know anything about programming or game creation? You don’t need to. Klik & Play is absolutely free to download, and learning it takes minutes. Join the next Klik of the Month.

Further Reading

- A relatively recent Interview with Anna Anthropy which mentions Klik of the Month.

- Anthropy recently presented her Starcade at the NYU Game Center; you can get the audio transcript here (scroll down a bit).